The release of Red Hill is a long time coming for writer/director Patrick Hughes.

An award winning director of short films, with the 2001 Tropfest winner The Lighter among his achievements, many expected Patrick to take the leap into feature films.

Instead Patrick became a successful commercial director, winning numerous awards and accolades for his work with Playstation, BMW, Mercedes, Xbox, and Schweppes, the later which saw him win a Gold Lion at the 2009 Cannes Advertising Awards.

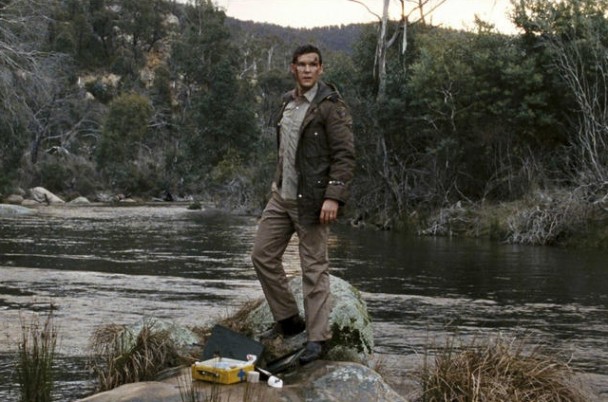

Now Patrick has released the low budget, high concept modern day western Red Hill, which stars Ryan Kwanten (True Blood) as a new police recruit at a small country town, who must contend with the vigilante actions of an escaped prisoner (Tommy Lewis, The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith).

In town to promote Red Hill, Patrick found time in his hectic schedule to talk to Matt’s Movie Reviews about westerns, independent filmmaking, and morality in film.

Enjoy!

Red Hill is essentially a modern western. What made you choose that genre for your first feature?

Moral code. That simple. When I grew up my dad was always trying to force the westerns on me, but I was too busy watching Star Wars, and then you get a bit older you realise that is just a western in space.

Personally, when I got a little bit older and matured a little bit more, then you really, genuinely understand what the moral code is and what every western is about, which is at what point do you take the law into your own hands and stand up for what’s justified in a world of wrong?

I was also really drawn to that location of high country Australia. A town like Omeo (Victoria), which was genuinely one of our biggest boom towns, had 40,000 people back in 1890, which is then the same population as Melbourne. There is a real tragedy to a town like that, when 100 years later, what’s happened to it? 120 people live there now, all of the people have left, and the industries have been shut down, so I felt like, “What happens to that town, which is sort of dying?” You end up with characters like Old Bill (Steve Bisley), who try to hang on to the past.

So it felt to me like the perfect setting for a modern day western, and certainly putting in that larger than life character...obviously Jimmy (Tommy Lewis) is an indigenous Australian, so that felt like a sort of wonderful parallel to the old western which I grew up watching, with the colonial days and the white man moving into America, which is very similar to Australia. I felt like that story hadn’t been told.

Does the moral code thing also come down to an honour amongst men?

Yes, absolutely. Essentially, the film is about revenge, redemption, and sacrifice. I have always been fascinated with stories where one man’s revenge can be another man’s redemption.

Pitching this film with this figure of darkness, this absolute evil who comes into this town, and slowly piece by piece starts to humanise the monster, and reveal that there is actually genuine loss and harrowing grief inside this monster, kind of like this Frankenstein.

I am a big fan of stories of revenge, if you pitch it right. You see a lot of revenge stories where it sort of just washes over you in the end, and you don’t get that emotional impact because not enough of these films justify to the audience...I remember watching Unforgiven with fist pumping in the air along a thousand other people in the cinemas, when Clint Eastwood was starting to cut loose in the pub with his shotgun, because it’s so justified.

It was such an exhilarating experience, because you’re like “Yeah! Take the law into your own hands.”

Would I be correct in assuming that Ryan (Kwanten) represents us, the audience?

Exactly. When I sat down to write the script, I sort of had just a hook which would be this guy busts out of prison, and comes back to kill the men who out him away. I had this image of Jimmy on horseback, riding through this small country town.

I used to drive from Melbourne to Sydney a lot when I was starting out as a commercial director, and I didn’t have the money to fly (laughs). Every time I would stay in these small country towns along the way, which I found interesting, these one pub towns.

When you sit there in town on a Saturday night, it is just empty, because you have these towns but no one lives in them. They all live on properties outside of the town. So you have all of this infrastructure that was built from the early days, but not one actually visits them and there is something actually creepy about it, and that sense of isolation is huge in terms of the western.

So in that germ of an idea, I felt there was no way into the story without a moral compass for the audience, that sort of classic screenwriting 101. Without the role of Shane, who are we to judge Jimmy’s actions? They’re pretty horrific so we can’t identify with them, and certainly Old Bill’s sense of justice and his sense of moral code we can’t identify with either.

The film is also, essentially, a changing of the guard. Shane Cooper represents a new breed of police officer, and he has his own sense of justice...it’s a city boy becomes the cowboy. The whole film was about, how do you get this guy to the line, and at what point is he going to take that gun and cross that line? If he’s gonna have blood on his hands, Shane wants to make damn sure that it is justified, which it is in the end.

|

| "I genuinely understood what the moral code is and what every western is about, which is at what point do you take the law into your own hands and stand up for what’s justified in a world of wrong?" - Patrick Hughes |

The film is very well cast. Did you write roles with specific actors in mind? Or were the specific archetypes in the western genre which appealed to you?

Something I love about the western is that it is lean, fast, and raw, and I wanted to write a story which was lean, fast, and raw, and quite simplistic, in the sense of it is like this stripped down version of the moral code.

Also there is this black humour throughout the film...I watch all of these westerns, and there are so many wonderful characters in them, that you end up with all of these crazy nutters in country towns with twisted view points.

I really like that hierarchy that Old Bill would have over this town. I remember when writing this script... I didn’t give him a name in the first draft. It happened really quickly, from sitting down to writing it, to being in Berlin, it was a really quick process.

But I remember when I wrote the first draft I just called Old Bill “The King”, and I called Jimmy “Evil”. It was all so I could remind myself, what would a corrupt king do if he was running this town? When you look at the hierarchy of it, small country towns have a lot of politics in them. A lot of people talk, a lot of business...you know, I felt like it was...

No secrets?

...yeah, it was the kind of place where since it was so isolated, corruption and people’s views can get a little bit twisted, which is what Barlow (the towns deputy, played by Kevin Harrington) represents.

So if you look at the hierarchy in the police station...Officer Manning (Richard Sutherland) is being groomed as the next Old Bill. And you get a narrative that Barlow is an individual that...something else the film features is the idea of the posse, that as a group these men commit horrific acts of violence, but as individuals they are all weak. Someone like Barlow is just weak. He doesn’t have what Shane has to stand up against Old Bill. He knows what has happened to his role, but he is just too weak to do anything about it. He’s too scared.

So we sort of broke it down to, “Who’s the pig farmer in town?” Who are the individual characters and what will they bring to the story? I was really trying to create sort of poppy archetypes, you know?

I know you are a big fan of George Miller, so having Steve Bisley from Mad Max...

...was unreal! I remember standing on the set with Steve, and the way we made this film was exactly the same way they made Mad Max. They made it with $700,000 and shot it in four weeks, which is pretty much what we did with Red Hill.

We felt like we were out there doing something way, way over ambitious. But it felt wonderfully liberating. The great thing about being in this small country town was that you could completely own it. So it was literally like, “Oh wow, we are setting fire to a five bedroom house”, and there are horses, rain machines, shoots outs, squibs and prosthetics....it was just every day we were doing something absolutely crazy. But you get such a wonderful scale going up to that region, and I wanted to make a film which was really cinematic and would not holdback on that.

That is why I love watching movies and my favourite filmmakers that present a more low budget film craft, kind of like going back to that old classic style of storytelling.

Jimmy Conway is one of the more memorable antagonists I’ve seen this year. You touched on his origins, yet how did he develop into the character seen on screen?

Well when I had the hook in, it kind of felt like “does this really mean anything?” I didn’t want to make a shoot ‘em up without him actually standing for anything.

I actually done an outdoor education 3 year course in high school as one of my subjects, and one of the great things about doing that is we went up into the high country and we spent a week with the indigenous elders there.

We walked through the bush with the elders for a week, and they were telling us stories and showing us these sacred burial grounds. It was sort of a combination of things, looking at these burial grounds which they had, and I’ll literally be in the middle of nowhere inside a national forest, and the burial grounds will be roped off so that the cows and horses who ride into this high country don’t trample all over them.

So that was something which really struck me when I was quite young. Then I was fortunate enough to do some Brumby chasing in Omeo when I was younger and listening to the locals up there. So everything Old Bill says in the town hall was legitimate. They have roped off the high country, they won’t let you ride horses through their anymore because the Greens got in and said, “You might trample on some protective wildlife”.

And of course every cattle farmer is like, “Fuck!” Then you have an erroneous bush fire which rips through the community, because we don’t any cattle up there grazing the undergrowth...there are all of these arguments, and they were little things which stuck in my mind, hearing these stories of areas being roped off for sacred burial grounds.

If you do the research you will find these things have happened in the past. Very early on you will find Jimmy is an indigenous gentleman, and it is also applying the genre of the west...

It reminded me of the Leone westerns, with the railroads and the industrialisation of the west...

Yeah! Because these are legitimate situations that are happening, especially in a town like Omeo. Back in the day they were always talking about putting a railroad out there, but for whatever reason it sort of collapsed.

So if you look like a town like Omeo, it is a frontier town, the last town before the high country, before you get on the horse and ride 6 weeks. So to me it felt like potentially it is a town that’s lost its way and dying, and you have a character like Old Bill who’s blind. In his mind what he is doing is justified. This town had an opportunity, that railroad could have saved them, but because of this sacred burial ground that Jimmy unearthed and went public with, in his mind it fucking killed the town. That was there last chance.

So it’s a real combination of all of those things. I just had a really strong image of Jimmy with a sawn-off shotgun on horseback, riding through this town on the dead of night. I felt like that’s really creepy. It’s sort of a nod to films like Deliverance, or The Thing, or Alien. I grew up watching all of these movies, and they all work on isolation...when you watch a film like Wolf Creek, you got that notion of “where the fuck do you run?”, and that sense of isolation in a town like Omeo, where the nearest place is 2 hours drive, if something bad went down what are they gonna do?

You take a character like Shane, and you virtually put him in the middle of it, working out the issue of trust and he doesn’t know who to turn too, so it all falls apart.

|

| "I just had a really strong image of Jimmy with a sawn-off shotgun on horseback, riding through this town on the dead of night. I felt like that’s really creepy" - Patrick Hughes |

There are mythological and even supernatural elements in the film. Jimmy Conway almost felt like a spirit of vengeance. Was that dimension there from the beginning, or did it develop over time?

Yeah, it’s also because like it was set from the very beginning that he was not going to say anything. By making him silent just made his actions all the more horrific. We can’t judge anything from what he does.

In a certain regard, when I was writing it his part he was this avenging angel of death, come to swoop away the sins of the country (laughs). I don’t want to bang the audience over the head with my political standpoint or view.... but it was certainly something I wanted to put in, and knowing these trackers and how they work, they kind of operate like ninjas, which is a weird parallel but it’s true in the way they work and breathe in the land, it is very sensory and they are very silent, moving around...when I was writing it was like this is Jimmy’s last supper. Very early on Tommy and I were talking about this is Jimmy’s last stand, and he knew it. He’s got nothing left to live for anyway.

I like that thing of, well here is this guy who has been in prison for the last 15 years, he’s going to take a moment to enjoy a piece of cake, because he hasn’t eaten any in 15 years, and it is a nice, sensory experience.

If someone told me, this is the last thing you are ever going to eat, I will take a moment to enjoy it. So we sort of laced all of that through.

You have called the film a passion project, since there was no distributor or government funding. Is such trial by fire beneficial to a young filmmakers career?

Well I reached a point of frustration. There were 4 scripts which I had written, and my first script got optioned 3 times when I was over in Hollywood and bouncing around Europe...I was quite young. But I had written a $40 million dollar action thriller, and no one is going to let you direct that kind of film until you make a movie, and it didn’t dawn on me because I had a bit of momentum in the script and I was doing really well with my shorts and commercial career.

But each time I began writing these scripts that progressively got smaller and smaller, and in the end I got so frustrated with the process, because I walked out of film school ready to make a feature, but it’s so hard to make your first film, and at the same time you want your first film to have an impact.

So I wrote this list of my favourite filmmakers, and noticed that all of them had mortgaged their house and sold body parts...if you look at Christopher Nolan, he shot his first film over the weekends, it took him 6 months and he used a 16mm camera, and he shot it, produced, and cut it himself.

A lot of people ask “Do you like wearing all of those hats?” Well part of it just necessity, and part of it saying “You know what? I’m just gonna go and make a movie”. So I got really inspired and I wrote a list, and it’s got George Miller, the Coen Brothers, Robert Rodriguez, and I’m a huge fan of the book Rebel with a Crew.

So one of the best pieces of advice I can give to younger filmmakers is, yeah, absolutely it’s high risk. There could have been the situation where we would have shot the film and if no one picked it up or bought it, I wouldn’t be sitting here and not have a film that no one is going to see. But that was a risk I was willing to take.

So yeah, it was a high risk gamble, but obviously it was wonderful in Berlin, where in 24 hours we sold every territory and to Sony in the states...

And here we are!

Yeah. (laughs)

The last few years has seen Australian filmmakers embrace genre films. Why the emergence of genre filmmaking?

I think there is a sub-conscious backlash, because we were making a lot of the same film for a good 10 years there. So I think a filmmaker like Greg McLean broke the ice with Wolf Creek, because we hadn’t made genre films for a good 10 years before that came out, and when it did it kind of exploded and proved to the world that if you come out with a universal story, that is also very Australian...I wanted to tell an Australian story that would work with an international audience as well.

Also, I wanted to make something really bad-ass! Literally, that was the word that was inside my head: I want to make something bad-ass! I wanted to make something to stood out.

I remember when Greg said to me, because he was the executive producer on the film and big inspiration, “What is your point of difference?” There are 5,000 films made every year, and you go to these film markets and 99% of them never get distributed and never see the light of day. So you’ve got to find what is your point of difference in the market place.

I remember when Greg set out to make Wolf Creek, people would say “You can’t make a film about that!” And Greg would say “Why not?”

It kind of feels the same with Red Hill. Giving an indigenous guy a sawn off shotgun, and just setting him loose on a small country town, is pretty confronting material and a lot of people were saying “Whoa!” People who haven’t seen the film were saying that I should not make a film about that, and I just say go and see the film and then we’ll talk (laughs).

Red Hill is currently playing in all cinemas through Sony Pictures. |

|